SCGA History

Part 2: 1920-1939

- Prologue: 1920 - 1939: Peace, Prohibition, Prosperity... and a Crash

- Chapter 1: A Golden Age of Golf Courses

- Chapter 2: A Golden Age of Golfers

- Chapter 3: Professional Golf and National Tournaments Arrive

- Chapter 4: Maturation, Growth and the End of an Era

- Chapter 5: The Dark Depression Days

- Conclusion: From Darkness to Light

SCGA History: Part 2

Prologue -- 1920 - 1939: Peace, Prohibition, Prosperity... and a Crash

From darkness to light, from bitter cold to blazing warmth, from depth to height. Whatever metaphor you choose, America in 1920 had emerged from four long cruel war years to the threshold of a dazzling new era, one that was marked by peace and prosperity and tempered by prohibition. It seemed as if it would last forever, but finally, an era characterized by flappers and the Charleston would evaporate into the worst of times: the Great Depression and World War II.

A confluence of events fueled the amazing decade that would become known as "The Roaring Twenties."

The great immigration wave of the last half of the 19th century, which had seen the United States population more than triple between 1850 and 1900, continued unabated as another 30 million people streamed onto America's shores in the first two decades of the 20th century.

California's growth was even more astounding. From just under 1.5 million people at the turn of the century, the state's population more than doubled to more than 3.4 million by 1920. Another 2.2 million would become California residents in the next 10 years.

Moreover, this was a confident, buoyant nation. A people who had just "won" the "war to end all wars" and had swept aside the ravages of "demon rum" were now ready to reap the benefits of those "great crusades." American industry -- riding the magic words of "assembly-line production" best exemplified by Henry Ford's thriving automobile company -- was ready to oblige. Mass production, coupled with the easy availability and growing acceptance of installment credit, sent the American economy soaring into the stratosphere.

Moreover, this was a confident, buoyant nation. A people who had just "won" the "war to end all wars" and had swept aside the ravages of "demon rum" were now ready to reap the benefits of those "great crusades." American industry -- riding the magic words of "assembly-line production" best exemplified by Henry Ford's thriving automobile company -- was ready to oblige. Mass production, coupled with the easy availability and growing acceptance of installment credit, sent the American economy soaring into the stratosphere.

Perhaps nothing so characterized America in the Roaring Twenties as its love affair with sports. Whether it was the victory aspect that satisfied America's pent-up need for winning or the outdoor element that appealed to an increasingly urbanized society, sports became deeply embedded into the American psyche during the 1920s. Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Notre Dame's Four Horsemen and a golfer named Jones all captured the imagination of the American public.

Even before Bobby Jones burst onto the scene in the 1920s, an amateur golfer named Francis Ouimet had captured the fancy of Americans by winning the 1913 U.S. Open, defeating famed British pros Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in a playoff at The Country Club in Brookline, Mass. Ouimet's victory gave golf a prominence with the American public that it has never lost.

It's also worth noting that the popularity of sports in general -- and golf in particular -- is due in large measure to the millions of prosaic words penned by such newspaper reporters such as Grantland Rice, Herbert Warren Wind, Dan Jenkins and Jim Murray. As Murray once noted: "Sportswriters may owe a lot to athletes but athletes owe everything to sportswriters."

From automobiles to sporting events, from John D. Rockefeller to Bobby Jones, the 20s proved to be a golden age, one that seemingly would never end... until "Black Monday" -- October 29, 1929 -- brought it all to a crashing halt.

Chapter One -- A Golden Age of Golf Courses

The golf tide in Southern California has always ebbed and flowed due, in large measure, to the region's financial fortunes, but the 1920s stand out as the first "Golden Age" of golf course architecture and construction in Southern California.

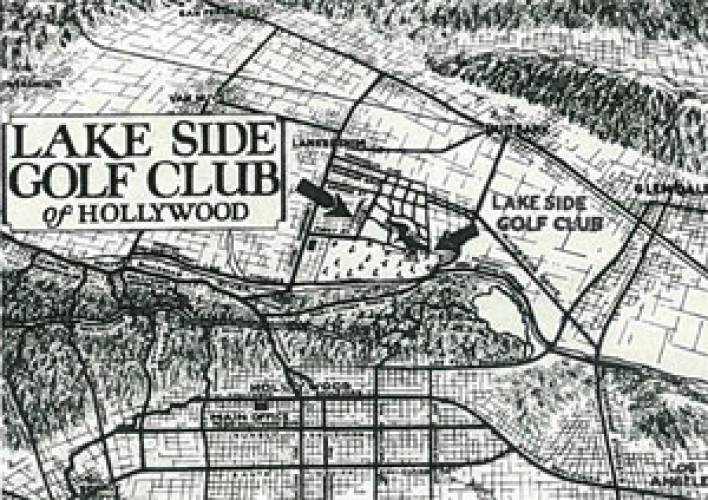

The sport of golf had captured the country and nowhere was that more evident than in Southern California. From 18 clubs with 1,371 members in 1919, the SCGA skyrocketed to 45 clubs in 1925 with approximately 20,000 members. Not all of these clubs survived the Great Depression of the 1930s or the wrecking ball as developers sought land on which to build more homes and business in succeeding decades. Nonetheless, many of the clubs built in the 1920s remain today as landmarks in golf course design.

That golf courses could flourish in what is essentially a vast desert was due, in large measure, to the miracle of irrigation. Several clubs experimented with hardy strains of grass and ways to keep it green. As long-time SCGA President Edward B. Tufts noted in his 1925 book, The History of Golf in Southern California, "A scant ten years ago, there was not a grass green or turf fairway in the Southwest. Greens were oiled sand and fairways were hard dirt. California golf was a joke and it seemed it had no future."

That golf courses could flourish in what is essentially a vast desert was due, in large measure, to the miracle of irrigation. Several clubs experimented with hardy strains of grass and ways to keep it green. As long-time SCGA President Edward B. Tufts noted in his 1925 book, The History of Golf in Southern California, "A scant ten years ago, there was not a grass green or turf fairway in the Southwest. Greens were oiled sand and fairways were hard dirt. California golf was a joke and it seemed it had no future."

To solve that problem, Tufts and his club, The Los Angeles Country Club, planted a patch of bermudagrass. "Almost over night (sic)," writes Tufts, "it made a smooth carpet of lawn. We then cut off the water supply and the grass turned brown and seemed to die. Even so it still presented a stiff brush that made a poor lie next to impossible. After it had apparently been killed we started watering it again and it came to life, turned green and started growing . . . Here was a grass that could not only exist but would thrive in California."

Another element of nature that contributed to the '20s golf course building boom was oil. Hundreds of people became rich when they struck oil in Southern California, from Bakersfield and the San Joaquin Valley to Santa Fe Springs, Signal Hill and Long Beach. One of the most notable of these was Alphonso Bell, whose oil riches would eventually be translated into Hacienda Golf Club and Bel-Air Country Club.

A third element that contributed to the proliferation of golf courses was real estate development. Developers looked at the success of The Los Angeles CC and Annandale Golf Club early in the century and realized that golf courses could act as a value enhancement to real estate prices. Moreover, hotel magnates saw how golf courses had significantly enhanced the renown of many resorts and hastened to either build or attach themselves to new golf courses.

Wilshire Country Club was a precursor of things to come when it was built in 1920. First, it was a course that brought additional prestige and value to its locale, Hancock Park, an area that was already one of the wealthier enclaves of Los Angeles. Moreover, its designer was Norman Macbeth, whose fame as a golfer (he was SCGA Amateur champion in 1911 and 1913) was widespread throughout the region and, indeed, the country. Thus, Macbeth might be said to be the forerunner of Jack Nicklaus and others whose golfing ability gave instant stature to their work as golf course architects.

Although the term "golf course architecht" had yet to be fully developed, several well-known designers fashioned courses in Southern California. Among the best-known and most prolific were George Thomas, Jr. (see pages 6 & 7) and Max Behr (see pages 8 & 9), but others were to leave their mark here, as well.

Although the term "golf course architecht" had yet to be fully developed, several well-known designers fashioned courses in Southern California. Among the best-known and most prolific were George Thomas, Jr. (see pages 6 & 7) and Max Behr (see pages 8 & 9), but others were to leave their mark here, as well.

Perhaps the most prominent was Alister MacKenzie, the Scottish-born architect who worked with well-known Southern California golfer Robert Hunter to design Cypress Point Golf Club and The Valley Club of Montecito, both in 1928. MacKenzie is also credited with designing Tijuana CC and with redesigning Redlands CC, one of the SCGA's five founding clubs.

One other person who would go on to become a respected golf course architect was William Park Bell, who came to California at 1911 and became caddie master at Annandale Golf Club.

Billy Bell served a storied apprenticeship. He was construction supervisor for Willie Watson (who designed, among others, The Olympic Club in San Francisco), and George Thomas, Jr. and is credited with making significant contributions to many of Thomas' designs (see pages 4-5).

In succeeding years, Bell designed and remodeled nearly 100 courses, some in conjunction with his son, William Francis Bell. Among Bell's finest works from the 1920s are the two courses at Brookside Golf Club in Pasadena, which date from 1928, and San Diego CC, which was built when the club relocated to its present Chula Vista location in 1921.

Chapter Two -- A Golden Age of Golfers

As was the case with golf courses, the quality of players in Southern California was also increasing rapidly. Many fine golfers continued to winter in Southern California and play in the Southern California Amateur and the California Amateur.

One was H. Chandler Egan, who had won the 1904 and 1905 U.S. Amateurs, captured the 1926 California Amateur and donated the trophy on which medalists' names are inscribed today.

Another was Willie Hunter, the 1921 British Amateur champion (and 1922 runner-up) who arrived at Midwick CC by train on the morning of qualifying for the 1923 SCGA Amateur and went on to defeat home-course hopeful E. S. Armstrong, 2 & 1, to capture the crown.

But more and more, Southern California golfers were being home grown. Some -- like George Von Elm -- migrated here from colder climes. Others -- such as Charles Seaver -- grew up in the area and then went off to college. A few, such as Von Elm and Pat Abbott went on to professional careers, but many elected to remain amateurs and competed for decades in local events.

During the SCGA's first 20 years, tournaments were dominated by what we now call mid-amateur golfers (age 25 and older). In fact, it wasn't until 1922 that the SCGA Amateur was won by a "youngster" (Von Elm).

Increasingly, Southern Californians were making their presences felt on the national scene, as well, none more so than Von Elm, who shocked the golfing world when he defeated Bobby Jones, 2 & 1, to win the 1926 U.S. Amateur at Baltusrol GC in New Jersey. It was Jones' only U.S. Amateur loss in five years.

Perhaps the most stunning example of the emergence of California golfers was in the 1937 U.S. Amateur Public Links Championship, which was held at Harding Park GC in San Francisco. Half of the 64-man field was from California and the finals was all-SCGA as Bruce McCormick edged Don Erickson, 1 up, in their 36-hole match.

Historical Note: The Many Faces of Max Behr

Chapter Three -- Professional Golf and National Tournaments Arrive

With more and more attention being paid to the West Coast, it was, perhaps, inevitable that professional golf would begin to make its mark in Southern California. As was the case with many things during the first quarter century of the SCGA's existence, it was Edward B. Tufts and The Los Angeles CC that led the way.

With the help of people such as Norman Macbeth, well-known magazine editor Scotty Chisholm and Jack Malley (president of the Southern California Professional Golfers Association), Tufts encouraged the Los Angeles Junior Chamber of Commerce to start up the Los Angeles Open and offer a record purse of $10,000 ($3,500 to the winner). William Randolph Hearst sent his star reporter, Damon Runyon, to cover the event, which was won by "Lighthorse" Harry Cooper at LACC's increasingly famous North Course.

The tournament's success (it remains as the nation's oldest civic-sponsored event) encouraged other tour stops, as well, although the concept of the tour as we know it today was barely in its infancy. In 1929, the Caliente Open was held in San Diego and its $25,000 purse became the largest offered.

The year 1929 was a "major" year for California. The U.S. Amateur was held that year at Pebble Beach, the first USGA championship to be west of the Rocky Mountains. The Professional Golfers Association of America (PGA) brought its championship to Hillcrest CC in Los Angeles in 1929. It wasn't considered a "major" at the time (the concept of "majors" wasn't solidified until 1930 when Bobby Jones won the U.S. Open, U.S. Amateur, British Open and British Amateur -- the so-called "Grand Slam"), but it was the first national championship to be held in Southern California. The following year, The Los Angeles Country Club hosted the U.S. Women's Amateur Championship.

In 1937, Bing Crosby, who three years before had moved to the exclusive San Diego County enclave of Rancho Santa Fe, invited a few golf professionals and friends from Hollywood to join him for a two-day tournament at the conclusion of the Del Mar racing season (where Crosby was a regular). Crosby called his tournament the "clambake" and after World War II moved it to the Monterey Peninsula where it became famous as the Bing Crosby Pro-Am (it's now called the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am).

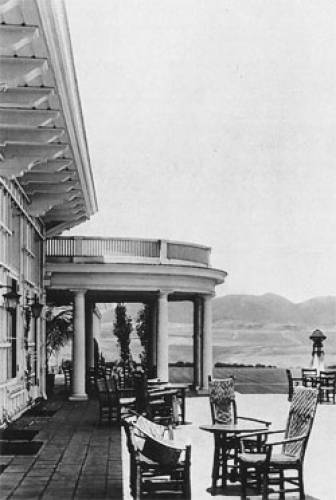

Historical Note: Hollywood and Golf

Chapter Four -- Maturation, Growth and the End of an Era

As the SCGA grew in size, it continued to emphasize its traditional programs. The SCGA Amateur Championship was held every year with new courses being added to the rota (see pages 14 & 15). As the tournament grew in popularity, a President Flight was added for net competition in 1934 and a Vice-President Flight came a year later.

Team Play continued to grow in popularity and in 1927 SCGA Director Peter Cooper Bryce donated a trophy that is still used today. Ed Tufts continued his duties as official handicapper, as well as president.

Perhaps the most shattering event for the SCGA was the death of Tufts in 1927. He had served as SCGA president for 28 years until, as an official resolution stated, "death made its unanswerable call upon Edward B. Tufts." But two years later, an even greater shock would hit the SCGA -- and the world -- when the Great Depression struck.

Despite the Depression, the association moved forward into new areas. In 1923, a women's auxiliary had been founded at Hollywood Country Club; 10 years later it spun off to become the Women's Southern California Golf Association.

As the number of public course began to grow in the 1930s (at the beginning of that decade, more than 80% of courses in the U.S. were private and only 700 -- 1.5% -- were considered public), the SCGA encouraged the formation of what is now called the Public Links Golf Association of Southern California. In 1934, the SCGA formed the Seniors Golf Association of Southern California.

The SCGA considered and rejected a proposal to allow Pacific Golf & Motor (which was edited by Jack Neville, designer of Pebble Beach and five-time state amateur champion) to be the SCGA's official publication. The concept of an official publication continued off and on for the next four decades until FORE Magazine was founded in 1968.

The SCGA considered and rejected a proposal to allow Pacific Golf & Motor (which was edited by Jack Neville, designer of Pebble Beach and five-time state amateur champion) to be the SCGA's official publication. The concept of an official publication continued off and on for the next four decades until FORE Magazine was founded in 1968.

In 1930, the SCGA began a turf research program in conjunction with the University of California at Los Angeles. Over the years, the SCGA has supported many such projects, including its current involvement with the Southern California Turf Research Council and turf management and research programs at UC Riverside.

The SCGA also began experimenting, hoping to establish a more uniform system of handicapping. One proposal, by golf course architect Max Behr, was to determine handicaps based on the number of pars made. Over the years, the SCGA evaluated several alternatives before dovetailing its programs with the USGA Handicap System.

In 1934, the minutes reflect that the SCGA established its first office "at a nominal cost" at the Detweiler Building in downtown Los Angeles. The office recognized the growing importance of the SCGA and the necessity to have a central clearing house for things such as record keeping and legislative action. The SCGA's first employee was hired a few years later.

During the 1930s, the SCGA was instrumental in encouraging state government to adopt a new series of water rates which recognized that water for irrigation should be priced at a lower rate. That same year, the association led a drive to defeat in committee a state legislature bill that would have imposed a penal excise tax on income at golf clubs. It would be the first of many such efforts over the years as, periodically, state and local governments sought to tax golf courses on their supposed commercial value rather than their "actual use" basis.

Chapter Five -- The Dark Depression Days

Few days in American history have been as wrenching as October 29, 1929. Almost overnight, the American juggernaut came to a crash and for the next decade, the Great Depression gripped the land; as NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw put it, "Economic despair was on the land like a plague."

Like virtually all of America, the depression caused severe hardships in Southern California and, without exception, golf clubs were not exempt. Although SCGA dues were just 10 cents per member, many clubs dropped out of the association, only to reappear on the rolls again when they were able to make good on their dues payments. The saga of many clubs well-known today was painfully chronicled in sometimes month-by-month "Perils of Pauline" style struggles over non-payment of dues. The number of SCGA member clubs, which had been 56 in 1930, dipped to 31 in 1938, but rebounded to 33 in 1939.

Even more significantly, many clubs -- including some which were well-established and highly respected -- closed their doors for good during the depression or the war years that followed, including Hollywood CC and Flintridge CC.

Perhaps the most notable was Midwick CC which hosted five SCGA Amateur championships in its first 15 years of existence. In fact, during the SCGA Amateur's first half-century, only The Los Angeles CC hosted more championships than Midwick. Former SCGA Amateur and California Amateur champion Charles Seaver remembers Midwick: "The reason it died wasn't really the Depression. Instead, it was that the club stopped reaching out for new members and eventually the membership just started dying off until it was too late." The club was eventually sold at auction in 1943 and re-opened as a public course, only to fall victim to encroaching development in the 1950s.

Virtually all other clubs struggled during the depression. Most developed creative ways of attracting new members or simply opened their doors to the public on a limited basis (a practice which the SCGA board tried to discourage). Several installed slot machines to augment income.

In many cases, however, it was one or two people per club who paid the bills and enabled the club to hang on. At Red Hill CC, for example, member Newt Trautman secured a $30,000 loan that forestalled a potential sale of the club when it defaulted on a note. When Oakmont Country Club went on the auction block in 1934, William Crenshaw bought the club for $42,000 to save it for its members. At Bel-Air CC, one member, Les Kelly, advanced $5,000 to pay Bel-Air's tax bill in 1944, and another member, John M. "Jack" Longan paid employees' salaries out of his own pocket from 1935-37. Longan typified the spirit of members who bailed out their clubs during the Depression: "The sun," he said, "will shine tomorrow.

Historical Note: SCGA Amateur Championship (1920-1939)

Conclusion -- From Darkness to Light

Longan was right, but it would take a decade before his prediction would come true. First would come the six horrific years of World War II, beginning with Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland, continuing with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and concluding only after millions of people were killed before the war's end in 1945.

However, with the end of World War II came an unprecedented period of prosperity: the "baby boomer" generation. It would also be an unparalleled period of golf course construction and another glorious era for Southern California amateur golfers.